ABCD

Rox Lee, 1985

with text by Merv Espina

28th February - 21st March, 2019

Courtesy the Artist, Merv Espina & Shireen Seno

**How to perform in front of a reptile:

Impressions of Rox Lee, auteur, amateur, autodidact**

“… since I started filmmaking I don’t have time to paint!”

Rox Lee, 1990 (1)

At a screening in an independent art space in 2011, one of Rox Lee’s Super 8 films became stuck in the projector. Being the projectionist at the time, I quickly turned it off and, with the artist present, thought it would be best for him to decide how to proceed. “I’ve done this before,” he said. “It’s very easy.” Relieved, I stepped back and watched him do his thing. He immediately started biting off whole sections of his film. This was the only print, no other copies existed. I watched in horror, unable to move. As soon as I could, I stepped in and said that I’d take over from there. “It’s okay,” he said. “Those were only a few seconds. You won’t miss anything.” The film was Silent Tattoo, a documentary short he shot during a fellowship in Japan between 1993 and 1994. Hearing stories from his peers about the wild, unpredictable Rox Lee, I never made the connection with this somewhat shy, humble, approachable man. That was in the past, I thought. He was no longer the guy who filed his front teeth to resemble shark teeth, no longer the notorious madman known for sporadic acts of defiant, Dadaist performance and sudden nudity. The guy who was punk before punk. To me, he was the cool uncle of the scene, consoling, encouraging, always ready to share a beer, ending every other sentence in puns and jokes, that funky guy flashing funny dance moves in underground rock gigs. Had I witnessed a glimmer of this wildness when he nonchalantly bit off parts of his own history? It took a while for it to sink in: Rox Lee is anything but nostalgic. He remains unsentimental about his past. And this attitude extends to his entire body of work, and how he treats it: always looking forward.

He is generous. Almost too generous. And very punk about it. In 1989, when some of his (then) young fans reluctantly asked for a contribution to their fanzine, Red Racket, the unofficial rag of seminal underground music venue red rocks, he promptly reached into his bag, took out a sketchbook, and ripped off a page to hand to them. He was already Rox Lee, the guy behind all these crazy films and a nationally serialized comic strip, “Cesar Asar.” He seemed unfazed in 2009 when Typhoon Ondoy caused terrible flooding in Metropolitan Manila and the surrounding provinces. He shares a house with his brother, the painter Romeo Lee, in a flood-prone area. The 2009 flood submerged the entire first floor, the part of the house where Rox Lee kept most of his personal archives — films, videos, photographs, drawings, and paintings — spanning three decades of practice. A little while after the flood, I asked about the incident, what happened to his works? Without pause, he smiled, and replied that he just let them float around for a bit. He let the flood take them.

Rox Lee, autodidact and artist best known for his work in film, came to this medium relatively late in life. Already past the age of thirty, and frustrated with his limitations as a writer, illustrator, and painter, he embarked on his first hands-on foray into film in a workshop organized as part of the Ateneo-Mowelfund Program for Artists in Cinema and Television (AMPACT). Drawn to the medium by its multidisciplinary nature, this first venture saw him as scriptwriter for Ted Arago’s directorial debut, Tronong Puti (White Throne, 1983). The film depicts a postapocalyptic cult worshipping a toilet bowl, in a cheeky, cautionary tale of nuclear holocaust. Those familiar with Rox Lee’s works in print could not have missed his unmistak- able brand of humor.

A year later, he made his own parable on nuclear disaster, The Great Smoke (1984). Made quickly in his garage without the aid of proper equipment, this Super 8 work continued the Dada-Surrealist brand of comic social commentary evident in his prose and comic strips. The film translated into moving image and animation the collage and illustration techniques with which he had been experimenting in his work for Jingle magazine. In the following years, he churned out a succession of award-winning works in Super 8 and 16mm — made both individually and with a revolving cast of collaborators — cementing his mark on the cultural topography: Tao at Kambing (Man and Goat, 1984), Inserts (1985), ABCD (1985), Lizard, or How to Perform in Front of a Reptile (1987), Ink (1987), Juan Gapang (Johnny Crawl, 1987), Prayle (Priest, 1987), Pencil (1989), Spit / Optik (1989), Moron’s Monolog (1989), Moron’s Hobbies (1989), and Mix 1 & 2 (1990).

With their films as their passports, he and his peers were finding themselves in international film festivals in Hong Kong, Singapore, and elsewhere, platforms that were early to champion a new brand of Asian cinema. Rox Lee was a signatory to the 1989 Manifesto of the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, which strove to define an Asian documentary aesthetic distinct from that of the West. The following year, the network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema (neTPAC) was founded in new Delhi, with filmmaker and Mowelfund director nick Deocampo one of its pioneers. The revolutionary spirit in late-1980s art and cinema went hand in hand with social and political change. Rox Lee and his Mowelfund peers were in the midst of all this, witnessing and participating in the 1986 eDSA People Power revolution and, thanks to an invitation to a German film festival, the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall.

Rox Lee is the enlightened amateur as auteur.

Many claim to have been mentored by him, though he doesn’t think of himself as a mentor figure. But his sphere of influence is unmistakable. he was witness and godfather to the emergence of new art forms that would later be known as media art, noise, sound art, etc. As always, taking advantage of accidents and chance, Rox Lee has become the unwitting “ignorant schoolmaster” of the Manila underground cultural scene. Filmmaker Regiben Romana was helping Rox Lee with the sound for a recently completed film. As a technician working for various nightclubs, Regi was technically proficient and knew his way around audiovisual equipment, but this know-how didn’t prepare him at all. Rox Lee wanted the glitches, the feedback, the noise, the accidents — everything that Regi hoped to avoid for a clean mix. Regi would later join Red Racket and Mowelfund stalwarts Jing Garcia, Maghiar Tuazon, Tad ermitaño, and others, to found the pioneering media art and noise outfit Children of Cathode ray in 1989. They continue to this day as the Philippines’ longest running sound and media art collective.

Tad Ermitaño, himself a filmmaker, too, likened his first experience of watching a Rox Lee film to a bomb explodingin his psyche, blowing away all his preconceptions of what a Philippine film should be and opening new worlds of possibility. Moreover, Rox Lee was approachable. Here was a role model that frequented the same dingy watering holes you did, someone with whom you could hang out and share a drink. But he didn’t tell you how to go about things. There was no advice, but always the pun, the joke,

the easygoing, self-defeatist manner. If you liked his works he encouraged you to go and make your own, to do it yourself, and he was always eager to collaborate.

While ready to adapt to new technologies, Rox Lee also embraced his unfamiliarity and limitations with them. he took in the misfires and unpredictable workings of (usually) hand-me-down, barely working, and salvaged equipment as part of his aesthetic. With an irreverent, sometimes even foolhardy pluck in exploring new and unconventional modes of storytelling, he was ceaselessly improvising, collaborating on new works and reworking old ones. Playing with technology while not necessarily commanding it, dabbling with things until they either exploded or yielded something cool, was an attitude unmistakably shared by local pioneers of art forms that had yet to find their proper nouns and definitions. Finding little support and few accommodating venues, these new practices emerged from a community of punks, goths, and underground rock-loving experimental filmmakers in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Red rocks, Club Dredd, and other underground venues were the incubators of these new practices, a function that would later be taken up by artist-run spaces such as Surrounded by Water, Big Sky Mind, Green Papaya Art Projects, and Future Prospects, to name just a few. Like the generation before them, these communities would also experiment with new media, modes, and strategies of art production, sharing a playful disregard for authority and established conventions. Many of the people involved were also part of bands and obscure subcultures around punk and noise music, zines, video art, and experimental cinema. Some even attended Mowelfund workshops in the late 1990s and early 2000s, by then being taught by the “students” of Rox Lee.

For his part, Rox Lee was still at the heart of the scene, hanging out and inadvertently mentoring the younger generations. In these emerging artists and platforms, he found a new audience and support system for his artistic pursuits, not just in the moving image. After many years of not exhibiting, he had a solo painting show at Surrounded by Water. He released a CD in his unique idiom of outsider folk music through the Kamias road records imprint of fellow filmmaker and multidisciplinary artist, Khavn de la Cruz. Rox Lee would also join Khavn’s noise performance ensemble The Brockas, comprised of Philippine indie cinema icons including Lav Diaz. This short-lived mid-2000s experiment was an explosion of spastic noise, nudity, and bodily waste, with occasional pop hooks thrown in, just to reel you in and spite you. Another Brockas alumnus, Tengal Drilon, would co-found the noise and experimental music label SABAW in 2006, and then the media art festival WSK in 2008. Along with other Mowelfund workshop participants including Jun Sabayton and Tado Jimenez, Rox Lee founded Sinekalye (Street Cinema). They continue to organize street-side screenings in unconventional locations, in squats, out- side rock clubs, and in any venue that will host them, spreading the gospel of DIY moving-image production to any- one who dares to watch and engage.

Rox Lee continues to influence younger artists working at the many inter- sections of cinema and contemporary art. In all his years of practice and for all his success, he has always been an artist’s artist, always on the periphery— though many of those he influenced have found mainstream success or have become industry leaders. Still, there are many others like him, who continue to pave their own paths. he may not have laid all the groundwork for Philippine experimental art, but one thing is certain: he inspired and supported the succeeding generations of artists who did.

- Rox Lee, Arthur Cantrill, and Corinne Cantrill, “The Films of Rox Lee” (interview), Cantrills Filmnotes #61–62 (May 1990), pp. 38–42.

Text courtesy Merv Espina. First published in association with the exhibition »Misfits «: Pages from a loose-leaf modernity, April 21–July 3, 2017, haus der Kulturen der Welt, curated by David Teh in collaboration with Yin Ker, Merv Espina, and Mary Pansanga. Exhibition and booklet are realized by the Department of Visual Arts and Film. Part of “Kanon-Fragen” under the artistic direction of Anselm Franke.

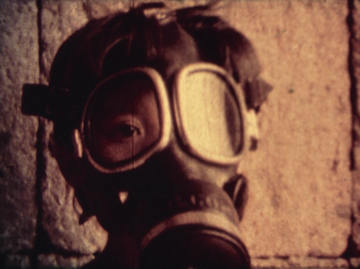

Rox Lee, Inserts, 1985 / 2011.

Still from Super 8mm film, transferred to HD, 5:21.

© Rox Lee, courtesy Merv Espina & Shireen Seno

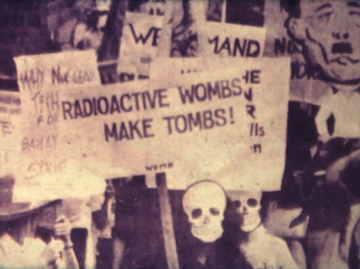

Rox Lee, The Great Smoke, 1984 / 2011.

Still from Super 8mm animation, transferred to HD, 6:00.

© Rox Lee, courtesy Merv Espina & Shireen Seno

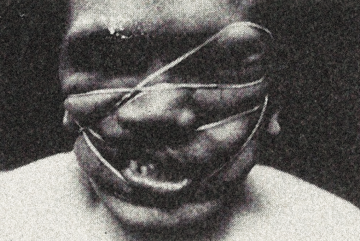

Rox Lee, Juan Gapang (Johnny Crawl), 1987.

Still from Super 8mm film, transferred to HD, 7:18.

© Rox Lee, courtesy Merv Espina & Shireen Seno

Rox Lee, ABCD, 1985.

Still from Super 8mm film (line animation and collage), transferred to HD, 5:22.

© Rox Lee, courtesy Merv Espina & Shireen Seno

German filmmaker Christof Janetzko gives a demonstration at Mowelfund Film Institute, Manila, early 1990s. From left: Lav Diaz, Lauro Rene Manda, Joey Agbayani, Ian Victoriano, Cesar Hernando, Patrick Purugganan, Teddy Co, At Maculangan, and Raymond Trinidad. Courtesy Cesar Hernando

Red Rocks Pub, 1989. From left: Winston Hernandez, Cesar Hernando, and Rox Lee arm-wrestling

with Pepe Smith. Courtesy Cesar Hernando

Rox Lee in the catalogue of the 6th Gawad CCP Awards (Cultural Center of the Philippines), 1992.

Courtesy Rox Lee